posted by k

posted by k

When I was quite young, I was fascinated by the cast gallery in the Victoria and Albert Museum. This was partly because of the stern notice on the door, forbidding children under 15 from unaccompanied entry. I assumed - and still think - this was because of the fragility of the exhibits though it may have been because of the cast of Michaelangelo's David. I was too young to find his nudity particularly interesting or surprising. There were plenty of nudes in the National Gallery and British Museum and, for that matter, on public statues. But although I gazed in fascination at other works - Donnatello's little David and the massive cartoon-stories on Trajan's Column, it was Michaelangelo's David I liked to see. I visited the museums with my younger brother and would lurk outside the cast gallery, looking for a friendly-seeming grown-up who would act as my escort. Nowadays the whole idea would fill parents and social workers with anxiety, but my younger brother and I came to no harm. After all, at eight or nine I was old enough to be sensible and independent on a day out.

It was David's expression that fascinated me. Was he confident or was he afraid? I could never decide from the smooth, white, imitation marble. I still didn't know years later, when I saw the original sculpture and outdoor, in Florence.

I didn't know what David was meant to signify: the idea that he signified anything beyond his own story would have seemed strange to me. Now I learn that he stood for Florence itself and that the huge figure represented small, vulnerable Florence as an embattled city state. David seems to have retained that meaning through the centuries as various rulers and governments have co-opted him. Even the wealthy and powerful like to think of themselves as vulnerable defenders of peace and liberty.

I grew up with different myths of vulnerability. Like most myths, they were founded on a truth. What happened to Britain in the Blitz was terrifying (so was the bombing of Dresden and Nagasaki) and the courage of Londoners and others was rightly praised. I heard enough of air-raids and fires from my parents to know that it had been very bad indeed. Living through bombing, coping with daily news of death and injury and simply carrying on took immense courage - a courage that became a way of daily life.

I grew up with different myths of vulnerability. Like most myths, they were founded on a truth. What happened to Britain in the Blitz was terrifying (so was the bombing of Dresden and Nagasaki) and the courage of Londoners and others was rightly praised. I heard enough of air-raids and fires from my parents to know that it had been very bad indeed. Living through bombing, coping with daily news of death and injury and simply carrying on took immense courage - a courage that became a way of daily life.

From tales of the Blitz, from the story of Dunkirk, I learnt a myth of Britain: plucky little Britain, defender of liberty and democracy, standing alone against the fascist foe. This was merged with later knowledge to suggest that Britain fought Germany because of Nazi treatment of the Jews and other oppressed groups (gypsies, homosexuals, communists, dissidents, etc.). That wasn't so, although many individuals joined up because of the known evils of Nazism. Britain fought because Germany invaded Poland and because Britain itself was threatened. The treatment of minorities was seen as a domestic matter. There was considerable anti-semitism in Britain, even during wartime, and the opposition to Jewish immigration in particular prefigures current prejudice against asylum seekers who flee to Britain from torture and death.

Suffering did not make Britain a better, more tolerant place. It didn't prevent Britain from pursuing brutal imperialist policies elsewhere. The myth of small, suffering Britain enabled people - including me - to look away from the truth. I didn't notice what was happening in the Chagos Islands. I've only recently realised that the barbarous mistreatment of the islanders - which continues as our current Labour government refuses to obey court judgments and let the islanders return - was part of a well-established imperial agenda.

We in Britain are so used to the idea of our country as a guardian of freedom that this reads like mad extremism. But what else can I call it, when I read the words of the chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir John Harding, in 1955? He had been sent to ensure Cyprus continued as a useful British base; his mission was to prevent independence at all costs so that Cyprus could remain as a useful base for operations in the Middle East. Sir John Harding wrote to the British cabinet that, if Cypriot self-determination were to be prevented, "a regime of military government must be established and the country run indefinitely as a police state." The British cabinet accepted Sir John Harding's advice. Ministers were happy to run police states elsewhere if they contributed to Britain's safety or economic advantage. That is what imperialism means.

It's one of many passages that struck me in a long, informative article by Perry Anderson on the recent history of Cyprus in the London Review of Books. I hadn't known much about the history of Cyprus before. When I was at school, the British press treated Archbishop Makarios as a figure of fun but he emerges from the LRB article as a figure of far more integrity than the British cabinet ministers, civil servants and soldiers who opposed him. The British government encouraged and orchestrated brutality for its own interests, regardless of the rights, well-being or lives of its Cypriot subjects. And when things went wrong, Britain's Labour government, under Prime Minister James Callaghan, asked the United States for help - "an instinctive reflex in Labour," Perry Anderson comments.

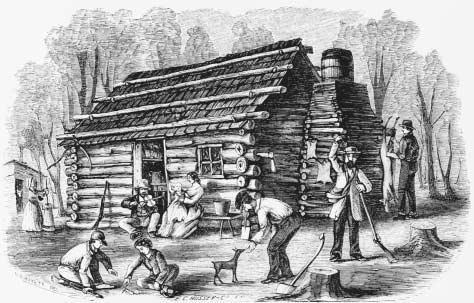

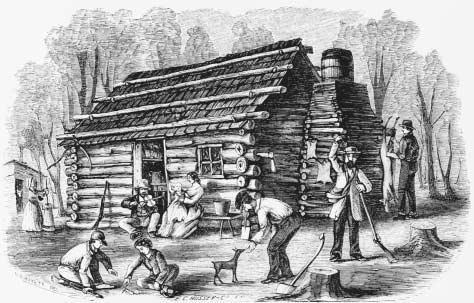

The United States also presents itself as small and vulnerable. The myth of the frontier is still strong and U.S. citizens rightly recall the courage of people who trekked across the country and built communities in the wilderness. But the wilderness wasn't uninhabited. As the new settlers established themselves and finally fought back against the oppression of imperial Britain, they also sought to subdue the original inhabitants of their country. George Washington outlined his strategy in his commands to General John Sullivan in May 1779:

"The Expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements, and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more."

"I would recommend, that some post in the center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition, with a sufficient quantity of provisions whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed."

"But you will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them."

Terror was Washington's weapon in the American War of Independence - or the American Revolution as it is sometimes known. The settlers who were becoming a nation thought terror a fair tactic to achieve the just society they envisaged - and that America's original inhabitants were proper victims. Less than three years previously, Washington had signed the Declaration of Independence, which included the words:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. - That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, - That whenever any government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, ..."

Today, Britain and the United States continue to use terror to further a modern imperial agenda. But we are constantly told that terror is what other people employ, and we have complex organisations - not fully accountable to democratic government - to defend us from the "terrorist threat". Liberty is curtailed in the United States and in Britain, with popular support.

The myths we hold dear talk of ideals - liberty, democracy, equality - which are still valuable. But unless we unpick the myths and look at historical facts - and our current practices - we'll find it hard to safeguard the values we should hold dear.

Labels: asylum seeker, Blitz, Chagos Islands, Cyprus, Declaration of Independence, democracy, equality, history, Homeland Security, liberty, MI5, myth, Nazis, terror, terrorism, United States, wartime